The Inside Report

A sample of news stories from past editions of Farmland Preservation Report.

CA appeals court rules in favor of farmland mitigation law

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor & Publisher

Published Dec. 2010

Almonds on ground on farm in Salida, Stanislaus County (Photo by Modesto Bee)

FRESNO, CA – California’s Fifth District Appellate Court ruled Nov. 29 that the Stanislaus County Farmland Mitigation Program (FMP) does not conflict with state law or exceed the county’s police power, claims made

by the Building Industry Association of Central California. The program will stand, and developers will continue to be required to provide for preservation of an acre of farmland for every acre their projects convert. The California Farm Bureau Federation and others were interveners in support of the county. Click here to view the ruling.

For development proposals converting 20 or fewer acres, the Stanislaus County program allows for either direct acquisition of a conservation easement on comparable lands, or the purchase of banked credits. If a developer of a parcel of fewer than 20 acres can demonstrate that no comparable land was available for conservation easement and no credits were available, a fee in lieu of purchase can be paid. But for parcels of greater than 20 acres, purchase of a conservation easement on comparable lands is required. The developer is solely responsible for negotiating and settling the easement purchase.

It is estimated that about 10 localities in California have enacted farmland mitigation programs.

A lower court found that Stanislaus County and the intervening Farm Bureau Federation failed to demonstrate a “reasonable relationship” between the FMP’s requirements and the negative impact of converting agricultural land to residential use. The lower court additionally found the county failed to show the FMP’s mandates would or could achieve its “ostensible purpose of mitigating farmland conversion.”

The appellate court found however, “that contrary to the trial court’s conclusion, the FMP mandates bear a reasonable relationship to the loss of farmland to residential development. As outlined in the County’s updated agricultural element, agriculture is the leading industry in the County generating an annual gross agricultural value in excess of a billion dollars into the local economy. Further, the elements that make the County so well suited for agriculture, i.e., favorable climate, flat land, available water and low-cost power, also make the County attractive for urban development, including affordable housing within commuting distance of major employment centers.”

The Building Industry Association claimed the farmland mitigation program was “arbitrary and without evidentiary support.” The appellate court disagreed, finding that, “Agriculture is the County’s leading industry. Real estate development that requires agricultural land to be converted to residential use has a deleterious impact on this valuable resource. Although the developed farmland is not replaced, an equivalent area of comparable farmland is permanently protected from a similar fate. To meet the reasonable relationship standard it is not necessary to fully offset the loss. The additional protection of farmland that could otherwise soon be lost to residential development promotes the County’s stated objective to conserve agricultural land for agricultural uses.”

Below is an abbreviated version of the full-length news and analysis in our Nation’s Top 12 survey enjoyed by FPR readers each year. This story is from Sept. 2010. See the latest survey in our Nov. 2011 issue.

Three counties move up in Nation’s Top 12 ranking

Preserved farm, Carroll County, Md.

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor & Publisher

LANCASTER, PA – The nation’s leading locally-operated farmland preservation programs preserved 7,460 fewer acres and received $16.4 million fewer local dollars in the last 12 months than in the year prior, but all programs operating in those localities preserved 18,313 farm acres in the period, which began Sept. 15, 2009, according to an annual survey conducted by Farmland Preservation Report.

The 12 counties have preserved a total of 668,364 acres through all programs. Last year’s total figure was 649,898. The survey tallies agricultural acres preserved by easement by government-operated programs, land trusts and township programs.

The counties combined committed $73.9 million to purchase agricultural conservation easements over the 12-month period surveyed, and committed $57.5 million for the upcoming 12 months, according to administrators. The totals do not include state and federal dollars.

Three county-operated farmland preservation programs – Carroll and Baltimore in Md., and York in Pa.- moved up in a ranking of the nation’s Top 12 local programs conducted as part of the survey, and most programs in the Top 12 have money to spend on new projects despite local and state budget crunches. A few programs have new policies and regulations to aid their twin goals of preserving farmland and keeping agriculture a working industry.

Lancaster County, Pa. remains the top program in the nation, reaching a preserved-acre total of 85,510. The county-run program logged 2,378 acres since the last survey in Sept. 2009. Lancaster County’s preserved-acre total is helped by the nonprofit Lancaster Farmland Trust, which has preserved 20,253 acres, 1,024 of those acres in the last 12 months, according to LFT deputy director Jeff Swinehart.

Lancaster County will continue to lead the nation for a long time – it has a 15,000-acre lead over second-place Montgomery County, Md., which has reached its preservation “build-out.” Third-place Berks, at its current level of activity, will overtake Montgomery in three years.

Carroll and Baltimore Counties in Md., and York County, Pa. moved up in the ranking from their 2009 spots. Carroll moved from 5th to 4th place, overtaking Chester County, Pa. Baltimore County moved from 7th to 6th place, overtaking Burlington County, NJ, and York moved from 9th to 8th place, overtaking Harford County, Md.

SOLAR POWER: CA WILLIAMSON ACT UNDER SIEGE

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor & Publisher

From FPR’s July 2010 Edition

Photo illustration by Teserra Solar of recently approved project in Imperial County

SACRAMENTO, CA – California’s budget crisis and the nation’s push for renewable energy have combined to put a hit on farm and ranchland protection in the nation’s top ag producing state. While the state pulled out of subsidizing counties’ property tax breaks to farmers last year, and probably this year, it is encouraging solar companies to propose panel installations on thousands of acres of farmland, including lands conserved under the Williamson Act.

Williamson Act lands affected by solar plans

In 2008, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed an executive order requiring the state’s utilities to produce 33 percent of their electric output from renewable sources by 2020. The order is testing the state’s long-standing resolve to protect farmland as the solar industry puts forth proposals that would blanket many square miles of farmland with solar panels.

According to John Gamper of the Ca. Farm Bureau Federation, the proposals are so numerous “it’s impossible to track them. I talked to one supervisor in Fresno County who said he has a solar guy in his office once a week. There are at least two dozen [proposals] in Tulare County right now, and they’ve been knocking on the doors in Madera, Merced, and San Benito.”

The largest proposal purportedly in the state, is one in which the State of California has entered into an agreement with Jiangsu Province, China, to build a 500-megawatt plant in Kings County, in the San Joaquin Valley. John Lehn of the Kings County Economic Development Corp. noted in the plan’s announcement, that Kings County edged out other localities because the county allows solar farms as a compatible use on lands protected under the Williamson Act, the state’s property tax abatement program for farm and ranchland that restricts development. An even larger proposal envisions covering 30,000 – 50,000 acres of what the county called fallow farmland in Kings and western Fresno County. Project boosters say the lands involved in the 500-mw project are characterized by high salinity and a lack of water.

The Williamson Act, known officially as the California Land Conservation Act, allows farmland to be taxed on its use, rather than on its development value or by Proposition 13, which limits increases in property taxes on non-Williamson Act lands. In exchange, enrollees agree to forgo land development for a minimum of 10 years.

In a recently issued memorandum, the Ca. Dept. of Conservation notes that an important aspect of the Williamson Act is “local rules (and the language contained in any specific contract at issue) play an important role in determining what is allowed under the local Williamson Act program.” This is particularly true in the Kings County case. According to the department’s statement, “Whether a proposed solar installation is compatible with the underlying agricultural use of the land depends almost entirely on the specific circumstances.” The memorandum names four ways Williamson Act contracts can be terminated, and a number of ways localities can determine solar installations to be a compatible use. But the memorandum clearly indicates the Department sees solar installations as converting ag lands: “It is important that proposals for the conversion of agricultural land to solar energy projects include a detailed site restoration plan detailing how the project proponents will restore the land back to its current condition if and when the solar panels are removed.”

Farm Bureau’s John Gamper indicated in an interview with FPR the state is making it easy for solar companies to use any agricultural land, contradicting a 1981 Supreme Court ruling.

“The Supreme Court says in Sierra Club v. City of Hayward that cancellation should be used in extraordinary circumstances only, and that they should use non-prime land or non-contracted land for public improvements, and this is essentially a public improvement if they’re saying it’s in the public interest. There’s a lot of other non-contracted land in California that could be used for solar panels…”

Williamson Act: Going for broke

It is estimated that farm and ranchland owners enrolled in the Williamson Act save between 20 – 75 percent on tax liability each year, about $150 million annually statewide.

California lettuce crop

And there’s the rub for the state. Since 1972, the state government has annually sent millions to counties to make up for revenues forgone in tax bills to farms and ranches. But those reimbursements, referred to as subventions, have become harder for Sacramento to send and last year the money stopped. Many say that will happen again this year, as state leaders continue to struggle with a $14.4 billion gap between projected revenues and spending in 2010–11, and a “lingering budget problem” of $20 billion “for years to come,” according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

In the wake of last year’s strike at subventions, several counties, such as Imperial County, say they plan to discontinue the program. That generally means that no new contracts would be taken, and none will be renewed as they expire. Other counties, especially those with fewer farms enrolled, such as Contra Costa County, are absorbing the loss.

“Our county isn’t huge – the loss is only $68,000,” said Contra Costa Agricultural Commissioner Vince Guise. “It’s being absorbed at this point, but our chief administrative officer is looking closely at everything.”

Some counties are taking a hit. The Stanislaus County Board of Supervisors is dealing with a $1.4 million loss due to the subvention payment that didn’t come for the 2009-10 budget year.

“They have tried to convey the message they don’t agree with the move,” said planner Angela Freitas. “Unlike some other counties, they haven’t taken any formal action, but are staying the course.”

In San Luis Obispo County, “supervisors say they will backfill,” the lost revenue, said planner Bob Lilley. “They put it as a high priority. It’s important to our county and very popular. It’s been highly successful here in protecting agricultural resources and controlling growth.”

The effectiveness of the Williamson Act in controlling growth has been debated over the years. A state map of enrolled lands shows that lands closest to urbanized areas are seldom enrolled.

But the long-term effects of tax incentives for land use restriction are apparent, according to Al Sokolow of the University of California-Davis Agricultural Issues Center. The law “has reduced leap frog development through the preservation of contiguous ag land acres,” he said.

Sokolow agreed, however, that the Williamson Act has not resulted in greenbelts around cities, the lands with the most development pressure.

“The generalization really applies to farmland in more remote areas.”

Sokolow disagrees with an assertion by the Ca. State Association of Counties that one-third of farms would not survive economically without the Williamson Act. “I have not seen any firm data on this point,” he said.

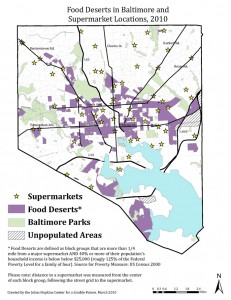

MAPPING PROJECT EXAMINES MARYLAND FOOD SYSTEM, FOOD DESERTS

Food deserts in Baltimore; what role for preserved farms?

BALTIMORE, MD – A data and GIS mapping project underway in Baltimore is focused on understanding who produces food for human consumption in Maryland, and who consumes that food.

The Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future is host to the GIS Food System Mapping Project, which has identified 800 farms in Maryland “that sell locally,” said project director Amanda Behrens.

An online interactive map will soon be underway, she said, that will allow users to select layers of data and produce their own maps. Three maps were recently released on the project’s website that detail food availability in the city. One map delineates neighborhoods that have no food stores within walking distance, defined as one-quarter mile, called food deserts. Behrens said the number of specialty crop growers who sell directly to supermarkets is unknown but could be determined through surveys the project will conduct.

Behrens said Baltimore City Schools attempted last year to arrange a cooperative as a means of procuring locally grown food, but was unsuccessful.

The maps are available at the website of the Center for a Livable Future at http://www.jhsph.edu/clf/programs/eating/proj_foodsystem.html

VIRGINIA SPURS PRIVATE SECTOR CONSERVATION

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor & Publisher

Originally published in FPR, March 2010 Edition

Virginia Gov. Bob O'Donnell

RICHMOND, VA – Before the Virginia General Assembly adjourned its budget session in mid-March it passed a bill that creates a permanent funding source for grants to land trusts and local governments to pay for easement monitoring. But while the legislature boosted the Commonwealth’s private sector-based land conservation with what appears to be upwards of $2 million annually, it mightily snubbed its Office of Farmland Preservation, allocating to it just $100,000 to assist 21 localities in purchasing easements on working farms.

HB 447, effective July 1, designates easement monitoring funds from transfer fees imposed on land preservation tax credits when they are sold.

The credit is awarded to landowners who donate easements.

Virginia’s Land Preservation Tax Credit program allows a credit on income tax of 40 percent of the value of land or interest in land that has been donated for conservation purposes. Through 2008, the Department of Taxation had awarded tax credits totaling $907 million for nearly 2,000 easements.

One of the features of the tax credit is that it is transferrable, that is, once awarded, it can be sold. The transfer option may be used by those whose income is not large enough to make the credit usable.

A fee was levied on such sales, with the revenues used to support administration of the tax credit. Now, those fees will be split, with at least half going to the Virginia Land Conservation Fund for distribution to local governments and conservation organizations for stewardship of preserved properties.

Until now the credit transfer fee has been two percent of the value of the donated easement or land, or $10,000, whichever is less. That cap will now be lifted. The estimated revenue from removing the $10,000 cap on the fee is $2 million annually above the current fee revenue, which was $2.1 million for FY 2009, indicating about $2 million will be available for easement stewardship grants. The grants will be awarded based a grantee’s three-year average for number of donated easements accepted.

According to Joel Davison of the Department of Taxation, collections from the tax credit transfers in this fiscal year, since July 1, have amounted to $1.5 million as of Feb., an amount equal to that collected in all of 2008.

Kevin Schmidt, director of the Office of Farmland Preservation, said he is disappointed the amount allocated to his program was not larger, but that following a legislative session that was “pretty dire,” “anything that isn’t zero makes me feel good.” The last allocation to the program, awarded by Gov. Tim Kaine in Dec. 2009, was $636,000, making this latest amount even more disappointing. But Schmidt said something is better than nothing.

“At least this way we keep running the mechanics of the program. If it were gutted, it would be much harder to bring it back.”

The state’s $4 billion deficit had all departments starting out with “low expectations,” Schmidt said.

The Virginia Outdoors Foundation is the state’s quasi-public entity that accepts easement donations, and currently holds 3,008 easements comprising 581,165 acres. VOF saw a sudden and dramatic increase in the number of easement deals beginning in 2000, the first year following enactment of the Land Preservation Tax Credit. Along with other similar entities, it stands to benefit most from the new stewardship fund.

In Oct. 2009, VOF completed a strategic plan in which the need for easement stewardship funding was front and center. “[T]he recent dramatic growth in conservation activity throughout the state has pushed VOF’s capacity to the limit,” the plan stated. “Over the next four years, it will be critical for VOF to maximize management efficiency and secure additional revenue to maintain its lead role in conserving new land and carry out its stewardship responsibilities.”

Virginia Blue Ridge farmland (photo by VDACS)

According to Jason McGarvey, legislative liaison for the VOF, donated easements, and the incentives that drive them, are perceived in the legislature as the technique carrying the day for land preservation in Virginia. He said donated easement benefits are reaching average income farms because of the transferrable feature of the credit.

“Where land values remain high, the donated value can trump what a locality is able to pay,” if the locality even has a funded PDR program – most Virginia counties do not. Farmers whose income won’t allow them to benefit from the tax credit, McGarvey said, can receive funding assistance from the state to offset the costs of an easement deal, “then they sell it. We don’t know who buys the credits,” McGarvey said, adding that they know of farmers using credit sale proceeds to “reinvest in the farm.”

McGarvey said he knows of cattle and dairy farmers in Southwest Virginia and in the Shenandoah Valley who have sold credits.

Conservation Partners LLC was formed eight years ago as a brokerage for the transfer of land preservation tax credits, handling deals from start to finish.

Taylor Cole, a principal in the firm, said they promote conservation easements to groups of farmers. They only work with properties that have solid conservation values, he said. That scrutiny is warranted not only by more vigorous reviews of conservation easements at the IRS, but by an audit by the Virginia Dept. of Taxation in 2004, which found claims with questionable easement valuations.

Cole said for the last four years his firm has paid 84 cents on the dollar for transferrable tax credits, with a six percent fee. The firm will pay a landowner’s credit transfer fee to the Dept. of Taxation and get reimbursed when the credit is sold, and also will pay the bills associated with easement deals. While Cole said his firm doesn’t collect data on the type of farm operations or income level of his clients, he said land-rich and cash-poor farmers make up part of their client base.

“For people not so wealthy, the ability to release the value in the land and to be able to sell the credits for cash, it’s a wonderful opportunity for these folks,” Cole said.

While some county PDR program administrators are seeing use of the tax credit program in their counties, others are not.

Ray Pickering, agricultural development director for Fauquier County, administers a purchase of development rights program funded through public and private sources. But the county also holds about 40 easements that were donated. Pickering’s department includes a staff person who monitors easements, but he said any grants awarded for stewardship will be welcome.

Pickering said the low level of funding for PDR will hurt county programs, particularly those that are just getting started.

Rachel Chieppa, PDR program manager for Isle of Wight County recently completed that county’s first purchase of development rights using an installment purchase agreement, protecting 630 contiguous acres in eight parcels. While local leaders are pleased with the closing, “our revenue from our local government is substantially less in 2011 and 2012 budget years. It will be hard to find any other funding, even though our board is extremely supportive.”

In Isle of Wight County, where nearly 70 percent of land in farms is cropland and the predominant crops are cotton and hogs, there are no VOF easements, Chieppa said.

“That’s unfortunate, but I wonder if that’s indicative of lack of education, lack of interest, or inability. I don’t run across a lot of farmers interested in donating whether for financial reasons or otherwise. My question is, is [the tax credit] helping the working farmer?”

Ed Overton of James City County, where agriculture makes up just $2.8 million in market value of products sold, said that of the eight farms the county has either completed easements on, or have in the pipeline, he felt some “would have been better off donating,” but “they all needed the cash.”

Overton said the distance between the $106 million available for easement donations and the $100,000 allocated for easement purchase matching funds is “not equitable.”

“It must be easier for politicians to open the door for a credit of $100 million than to appropriate $100,000. If they were really serious about preserving prime farmland, we ought to be saving the very best that’s left. I would just as soon see them cut the tax credit to $50 million and put $50 million in the farmland program.”

But Heather Richards, director of land conservation for the Piedmont Environmental Council, said the tax credit has made land preservation possible all over Virginia, something that was not happening prior to the tax credit.

“The transferability is the key for making the tax credit useable statewide,” Richards said.

Richards said prior to the tax credit, only 19 of the Commonwealth’s 98 counties had more than 1,000 acres protected. Now, that number is 70.

“The tax credit is not a panacea. There’s still a need for PDR. But the spread of land conservation across the state is remarkable.”

Copyright 2010 by Bowers Publishing Inc.

NEW JERSEY PRESERVED FARMS CAN BUILD ENERGY PLANTS

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor, FPR

Published in Farmland Preservation Report, Jan. 2010

Soybean fields are becoming hosts to wind turbines

TRENTON, NJ – In New Jersey a bill was signed into law Jan. 16 that will allow farms, including preserved farms, within certain limits, to build wind, solar or biomass energy generation facilities. Under S 1538, energy generation on preserved farms will be allowed to exceed farm use by 10 percent, or alternatively, the plant will be allowed to occupy up to one percent of the land. The new law will take effect July 1.

Under the law, farm owners will be required to own the facility and can sell excess generation to reduce energy costs on the farm through net metering. Under New Jersey law, net metering allows excess generation to be credited to the customer’s next bill at the retail rate.

Preserved farms in New Jersey, many of which are engaged in horticultural or other greenhouse operations that consume large amounts of energy, will be allowed to construct energy plants, with approval of the State Agriculture Development Committee. SADC’s review will be confined, under the law, to determining whether a proposal will “interfere significantly” with agricultural use; whether the facility will be owned by the landowner; will be used to provide energy to the farm “either directly or indirectly” or will reduce energy costs on the farm; and, finally, the SADC will review whether the proposed facility will either occupy no more than one percent of the land, or, will produce no more than 10 percent excess energy. The only other determining factor in approval will be comments from an easement holder, which would be notified by SADC. Easement holders or co-holders will have 30 days to comment, and SADC will have 90 days from receipt of an application, to approve, disapprove or approve with conditions.

Ag/energy defined for tax purposes

For the purposes of use value assessment for taxation under the state’s 1964 farmland assessment law, “agricultural use shall also include biomass, solar or wind energy generation,” the legislation states, which, according to SADC executive director Susan Craft, is distinguishable from redefining agriculture or even agricultural use generally.

The new law “acknowledges that alternative energy generation is something that can happen to a limited degree” without turning a farm into a power station, Craft said. It is a subtle distinction, she added, between allowing, for taxation purposes, the inclusion of energy production as an agricultural use, and changing the state’s definition of agricultural use. SADC strongly objected to changing the definition of agriculture or agricultural use when the bill was introduced in 2008.

The law states that no income from power or heat sold from biomass, solar, or wind energy generation may be considered income for eligibility for valuation, assessment and taxation.

New Jersey’s agricultural land values and agricultural property taxes are among the nation’s highest even with use value assessment.

According to Tom Beaver of the New Jersey Farm Bureau, the agricultural use provision in the bill was put in to extend protection of the new farm uses under the state’s right to farm law.

The Farm Bureau is “pretty comfortable with how the bill turned out,” Beaver said, and plenty of farmers are interested in energy generation.

“We had a series of workshops last year, and we had packed houses,” Beaver said.

The SADC and the Department of Taxation will write the rules along with agricultural management practices for biomass energy generation on commercial farms, including standards for management of dust, odor and noise. The state Board of Public Utilities will provide technical assistance to SADC.

Preserved farm in Burlington County sold at auction by SADC

The advent of solar, wind and biomass production on farms in New Jersey will be documented every two years by the Dept. of Agriculture, which is charged with reporting on facilities constructed under the new law, detailing “the extent to which existing structures, such as barns, sheds, and silos, are used for those purposes, and how those structures have been modified therefor; the extent to which new structures, instead of existing structures, have been erected.”

According to Craft, the SADC will meet with the Department of Agriculture this month and within several weeks after that distribute guidance on the new law.

“We’ll develop a coordinated approach because this is pretty far ranging in what was amended, we want to make sure all the agencies have an understanding of the bill,” she said.

Farmers buoyed by Christie administration

The New Jersey Farm Bureau has applauded the Christie administration’s support for agriculture on a number of fronts saying agricultural interests are assured of a reversal of circumstances from two years ago when the Corzine administration attempted to ease budget deficits by eliminating the Department of Agriculture. That move brought a roadblock of tractors and horses to the state capital and an appeal from the public. Upon taking office, Gov. Chris Christie quickly made it known he would keep Agriculture Secretary Doug Fisher on the job – a move supported by the State Board of Agriculture. Among other moves, the Christie administration will propose more funding for the Jersey Fresh marketing program, which dropped from $1.6 million 20 years ago to just $150,000 last year.

According to Dept. of Agriculture statistics cited by the Christie transition team’s agriculture subcommittee, the Jersey Fresh program generates $54.49 of output for every dollar spent by the state. Data from 2003 indicated that $1.16 million spent on the Jersey Fresh program increased fruit and vegetable cash receipts by $36.6 million and created an additional $26.6 million in economic activity within agricultural support industries, the report stated.

The NJ Department of Agriculture is among the state’s leanest divisions, with 217 employees, down from 271 in 2005 when a systematic reduction began.

The governor and the bond referendum

The governor’s transition team agriculture report called for dedicated funding for farmland preservation – a task for the legislature – but also stated the governor would have to decide when to issue the bonds voters approved.

“The current real estate market conditions present an opportunity to purchase easements and permanently preserve more farmland than would otherwise be possible,” the transition report stated. “An early decision on the bonds will give the county, local and non-profit organizations that partner with the SADC in the preservation effort adequate notice regarding the Spring 2010 funding cycle.”

Ralph Siegel, executive director of the Garden State Preservation Trust, said bonds would not be issued until funds are needed for specified projects.

“The word we are waiting for is the green light to begin preparing project lists for appropriations.” Siegel expressed doubt such word would come before next summer.

Voters approved a bond referendum last fall when they elected Christie governor, although he opposed borrowing for open space. Yet bond issue has been the only funding source for farmland and open space preservation in New Jersey. The bond referendum is not binding upon the new governor, who must grapple with the state’s $1.52 billion current year deficit.

The legislature has been no help in the dedicated funding arena. While a number of ideas have been floated, years of discussions have resulted in no agreement on a source for dedicated funding for the Garden State Preservation Trust Fund.

The New Jersey Conservation Foundation has called on Gov. Christie to move forward with the bond issue. Michelle Byers, executive director said New Jerseyans voted to borrow money for open space preservation no matter what.

“They did so in spite of a shaky economy, high unemployment and worries about taxes and personal finances. …It’s important for Gov. Christie to keep the funds flowing, issue the bonds expeditiously and pursue a long-term permanent funding source. Uncertainty or gaps in funding will mean lost opportunities.”

New Mexico enacts $5 million land fund

BY DEBORAH BOWERS, Editor & Publisher

Originally published in FPR, March 2010 Edition

Gov. Bill Richardson signs Heritage Conservation Act

SANTA FE, NM – Gov. Bill Richardson signed into law March 8 legislation that creates a land preservation program with $5 million in initial appropriations. The program will be administered by the state Department of Energy, Minerals & Natural Resources (DEMNR), State Forestry Division.

Agricultural conservation easements are among the projects authorized under the Natural Heritage Conservation Act, which will award grants to local governments, which can in turn award monies to nonprofits. DEMNR was authorized to either hold or co-hold easements with local governments or nonprofits. No dedicated funding source was established.

Agricultural easements will compete with projects focused on water quality, forests, wildlife, natural areas, outdoor recreation and cultural and historic sites. Amount of matching financial support is among the criteria for prioritizing projects submitted for consideration.

The goal of the State Forestry Division is to publish the rule for the new program by June 30, according to department spokesperson Jodi McGinnis Porter. “But that may not be doable – it’s not written in stone,” she said.

Michael Scisco, conservation specialist with the New Mexico Land Conservancy, said about 85 percent of the 80,000 acres the organization protects are agricultural. The federal Farm and Ranchlands Protection Program (FRPP) will figure significantly into matching funds for the new state dollars.

“We have some projects ready now for federal funding,” he said. Easement activity for the organization, which has just four employees, has doubled each year over the last two years, Scisco said.

One of the reasons for that is the state’s new land conservation tax credit, passed in Jan. 2008. The program allows a deduction of 50 percent of appraised easement value up to $250,000 per individual donor. The credit can be applied for up to 20 years. Also, like Virginia’s Land Preservation Tax Credit (see p. 1, this issue) it is transferrable. Since passage, the Conservancy has seen only “a modest increase in easements. Outreach needs to be done,” Scisco said. “We’re seeing it make traction now. This is the most incentive we’ve had, ever.”

According to Scisco, for “land rich and cash poor” operations, the tax credit “helps a little bit.” He said several tax credit brokers work the state.

NRCS in New Mexico has had $3.7 million in FRPP funds to acquire 12 easements covering a total of 3,215 acres. Sponsors include the Corrales Farmland Preservation Committee, the New Mexico Land Conservancy, the Rio Grande Agricultural Land Trust, the Taos Land Trust, and state agencies.

Judge rules Stanislaus County farmland mitigation plan unconstitutional

Published in Farmland Preservation Report, July 2009

MODESTO, CA – A Stanislaus County Superior Court judge has ruled that the county’s plan to require developers to preserve as much farmland as they develop is flawed because the plan does not adequately identify the nexus between farmland loss and new home construction. The ruling, filed in June by Judge William Mayhew said the law was unconstitutional because the county failed to show a “reasonable relationship” between the mitigation rules and residential development.

The Building Industry Association of Central California brought the suit following passage of the law in Dec. 2007. The group said it was not consulted early enough in the legislative process, and that the law singled out residential builders, exempting commercial and industrial development. The group claims 300 members, all homebuilders.

A number of localities in California have farmland mitigation programs, including Brentwood, Monterey and Davis.

Despite the judge’s ruling, Stanislaus County has other defenses against farmland loss. Voters in Stanislaus County last year approved a ballot measure that keeps supervisors from approving housing developments outside of cities without further voter approval.

NRCS reverses stand on contingent right

Published in Farmland Preservation Report, July 2009

WASHINGTON, D.C. – More than a page in the Federal Register of July 2 is dedicated to explaining a reversal in NRCS’s position, held since release of the Interim Final Rule (IFR) in January, that inserting a federal contingent right of enforcement into deeds of easement funded partially by the Farm and Ranchland Protection Program (FRPP) makes the federal government party to the easement and triggers federal title standards. The “correction” released July 2 defends the former position as “sound reasoning,” but cites parts of the federal code that allow a new interpretation, parts that apparently were interpreted differently before.

“This correction to the January 16, 2009, interim final rule clarifies that the right of enforcement is a condition placed upon the award of financial assistance and, therefore, does not constitute an acquisition,” the summary states.

“Despite the sound reasoning provided in the preamble, NRCS believes that it should reconsider its original interpretation because the continued adherence of Federal procedures for land acquisitions to FRPP transactions is counter to the express and implied Congressional intent gleaned from the FRPP statutory changes, the Manager’s Report, and the associated legislative history,” the explanation states.

The trouble began with the legislation passed by Congress that required a contingent right of enforcement. The NRCS now states that the statute calls for the “inclusion” of the right to enforce, not the “acquisition” of the right, and that the USDA evidently is not purchasing the right, and therefore “NRCS believes that the terms chosen, when viewed in the context of the overall framework of the program, indicate that the contingent right of enforcement is not a Federal acquisition of a real property right intended to trigger Federal procedures such as the DOJ Title standards.”

An additional comment period was provided that ends Aug. 3.

Farm Credit examines urban edge ag

Published in Farmland Preservation Report, Sept. 2009

WASHINGTON, DC – The Farm Credit Council will release a report in the coming months that examines the state of agriculture in the nation’s urban edge communities with a focus on agricultural economic development. According to report co-author Robert Heuer, a contributing editor of FPR, the report “examines public policies at all levels of government that can support agricultural development along the urban edge. It makes the case for an overarching policy framework that combines continued support for farmland protection programs with an integration of food-and-farming enterprise into traditional economic development programs.”

The report builds on the work of professor J. Dixon Esseks of the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Esseks completed a study last year that examined 15 urban-edge counties’ agricultural economies for signs of growth or sustainability. The FCC report examines one of Esseks’ study sites in Orange County, NY.

According to a draft of the report, three Farm Credit institutions, First Pioneer, Ag Choice, and MidAtlantic, “are helping to create a food-policy template for metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs).” The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the MPO for the Philadelphia region, has taken the lead in examining its regional food system.

According to Heuer, MidAtlantic loan officer Jay Shannon took part in the Philadelphia food system study “because he saw an opportunity to both expand his own network of contacts and supply a Farm Credit perspective.” Shannon told Heuer: “As the general public becomes more interested in where their food comes from and how it’s produced, people involved in production agriculture need to be at the table…”

According to Gary Matteson, Farm Credit Council’s vice president for Young, Beginning, & Small Farmer Programs, the dramatically increased demand for locally-produced food creates a boom market for farmers on the urban edge. That creates “a strong economic rationale to stabilize farming communities in transitional geographic locales where suburbia historically becomes the dominant land use.”

Publication of the report moves the Farm Credit Council closer to its goal of identifying pro-agriculture land policy, he said.

Matteson credited 25 years of farmland preservation efforts in metropolitan regions in the East as providing a foothold for urban edge farming. He said that has given rise to the need for economic development policy that will help rebuild agricultural economies that can meet food needs in those regions.